This blog, which was originally published by the Met Office and written by Applied Scientist Rebecca Sawyer, features output from the UKCR Climate Service Pilots work package.

Health is already impacted by the weather, with heat in particular causing heat-related illnesses, exacerbating existing heath conditions and excess deaths. In a changing climate, these impacts can be expected to increase. Urban areas are particularly vulnerable to changes in heat and as more people move into urbanised areas, it is important to understand how extreme heat will affect health and how these impacts can be minimised.

Extreme heat

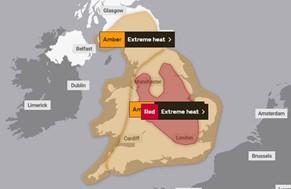

Last year, the UK experienced an unprecedented heatwave in July, where temperatures exceeded 40°C for the first time. This was a milestone in UK climate history, which was complemented by the first ever red severe weather warning for heat issued by the Met Office. Some areas of southern England recorded their highest ever temperatures by extraordinary margins of 3-4°C.

A Met Office study has recently been supported by the World Weather Attribution, which found that the likelihood of seeing 40°C in the UK has been ‘rapidly increasing’ and what once would have been an extremely unlikely event without climate change, has now become an unmistakable possibility. Both studies found that human induced climate change has made the chance of 40°C in the UK about 10 times more likely when compared with pre-industrial levels.

According to an analysis by the Office of National Statistics, from 10-25 July 2022, spanning the dates encompassing the new record temperature was hit, excess deaths were 10.4% above average for that period. This short-term increase in mortality is common during heatwaves. For example, the 2003 heatwave accounted for over 2,000 excess deaths in the UK: and in 2019 a heatwave which caused temperatures in England to reach 38.7°C caused 892 deaths. Direct increases in mortality and morbidity are usually amongst the most vulnerable groups which include people aged 75 years and over, infants and those with chronic medical conditions. These effects can be expected to increase especially among the elderly as the demography of the population shifts to include an increasing proportion of old-age citizens. High temperatures can also lead to an increase in heat-related illnesses such as heat stroke and heat exhaustion. Symptoms include nausea, dizziness, muscle weakness and high body temperature.

Urban heat island effect

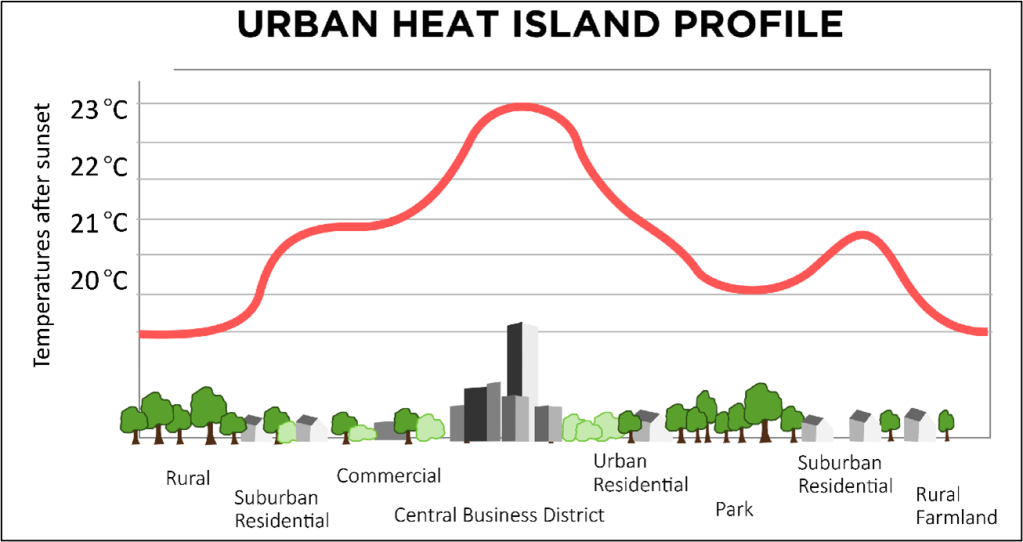

Living in a city can increase vulnerability to heat. Many deaths during heatwaves occur because of the combined effect of high temperatures and the urban micro-climate. In addition to background warming an additional factor facing city residents is the urban heat island effect. Buildings absorb rather than reflect the sun’s heat, and waste heat from air conditioners and vehicles can add warmth to the surroundings, increasing temperatures. Additionally, tall buildings and narrow streets reduce wind speeds, and the removal of trees reduces the natural cooling effect of shading and evaporation. Air pollution can also cause the effect of a micro greenhouse gas layer, stopping heat from radiating back into the atmosphere.

As more people move to urban areas in the UK, more people will become vulnerable to changes in climate and extreme weather events. Heat risks in urbanised areas can be minimised by utilising the amount of green space available, for example by planting trees in open spaces and in the streets. Heat reduction policies and rules could also be put into place at a local level.

Raising awareness

It is also important that local communities are educated about the risks associated with heat. Four in ten adults in England think heatwaves are “a normal part of summer”1 and have positive views about hot weather. Most people do not see heatwaves as a threat so are less likely to take protective measures. Additionally, most people in England do not consider themselves as at risk from the heat, even those from high-risk groups including elderly adults ages 75 and over. If the impacts of heatwaves that are posed by climate change are not clear, people are more likely to be exposed to the risks. It is important that people understand the real dangers of extreme heat and prepare for this, particularly as the climate changes and these events become more frequent, intense and of longer duration.

Utilising climate information for adaptation

Cities therefore need to be informed by the latest climate research and observational data to increase their ability to adapt to climate change and minimise these risks. At the Met Office, our Urban Climate Services team have created Heat Packs which consist of fact sheets containing information about how extreme heat events may change this century due to climate change. The Heat Packs have currently been generated for Bristol, Belfast and Hull. This work has also been combined with socio-economic data to understand which areas are more vulnerable to heat risks within the city. These Heat Packs can be used to understand the risks of heat in particular cities so that these areas can be better prepared against extreme events as we make our way into an uncertain future. This is supported by the Climate Programme Manager from Belfast City Council who said, “The Belfast Heat Pack is an important resource for Belfast and is being used to support both city and council climate planning and the development and delivery of climate projects such as the UPSURGE project and Belfast One Million Trees Project. We need to understand the impacts of heat on the city and on our residents as we plan for future climate changes and the Heat Pack is extremely helpful in supporting that”.

1. British Red Cross, (2021). ‘Feeling the heat: a British Red Cross briefing on heatwaves in the UK’. [online] Available at: Feeling the heat: a British Red Cross briefing on heatwaves in the UK | British Red Cross